CONTROLLING SOCIETY/ CONTROLLING THE STATE:

CRIME AND CORRUPTION WITH A FOCUS ON MEXICO *

Stephen D. Morris

Middle Tennessee State University

Abstract. At a fundamental level, crime and corruption represent the failure to effectively control society (crime) and the state (corruption). Despite the fact that many countries like Mexico face problems in both areas, the literature exploring the links between the two remains limited. This paper explores the intersection of crime and corruption, drawing on the Mexican case for examples and discussion. After defining and differentiating the two concepts to broadly encompass violations of the rule of law by citizens (crime) and state officials (corruption), the paper reviews the handful of empirical studies exploring the crime-corruption linkage. It then turns to a discussion of the issue of causality, detailing how crime—under certain conditions—facilitates corruption and corruption nurtures crime both directly and indirectly by way of a set of intervening variables. The paper highlights the common underlying determinants influencing both factors and examines the scope and reach of the model. It concludes by briefly laying out the next steps in the broader study of the interaction of state controls over society and societal controls over the state.

Keywords: crime, corruption, society, state, crime-corruption linkage, Mexico.

Copyright: © 2015 Morris. This is an open-access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source, the Tractus Aevorum journal, are credited.

Correspondence to: Steven D. Morris, Department of Political Science and International Relations, Middle Tennessee State University. 1301 E Main St, Murfreesboro, TN 37130, USA. E-mail: Stephen.Morris[at]mtsu.edu

УДК 323

ПРОБЛЕМЫ КОНТРОЛЯ В ОБЩЕСТВЕ И В ГОСУДАРСТВЕ:

ПРЕСТУПНОСТЬ И КОРРУПЦИЯ НА ПРИМЕРЕ МЕКСИКИ

Аннотация. На фундаментальном уровне преступность и коррупция свидетельствуют о неэффективности контроля в обществе (преступность) и в государстве (коррупция). Несмотря на то, что многие страны, как и Мексика, сталкиваются с проблемами в данной области, исследователи нечасто изучают взаимосвязи между преступностью и коррупцией. В данной статье рассматривается взаимовлияние преступности и коррупции на примере Мексики. Автор определяет и дифференцирует данные концепты для того, чтобы охватить широкий спектр правонарушений со стороны граждан (преступность) и государственных чиновников (коррупция), и на этой основе он проводит эмпирические исследования в контексте взаимосвязи преступности и коррупции. Также автор рассматривает вопрос причинно-следственных связей, уделяя особое внимание тому, как преступность – при определенных условиях – способствует коррупции, а коррупция создает питательную среду для преступности, как прямо, так и косвенно, при наличии ряда дополнительных переменных. В работе подчеркиваются общие детерминанты изучаемых феноменов и рассматриваются возможности применения предлагаемой модели. В заключение автор кратко обозначает следующие шаги в рамках более широкой проблематики исследования взаимосвязей в области контроля государства над обществом и общественного контроля над государством.

Ключевые слова: преступность, коррупция, общество, государство, взаимосвязь преступности и коррупции, Мексика.

Introduction

At a fundamental level, crime and corruption represent the failure of a government and a people to effectively control society (crime) and the state (corruption). But despite the fact that many countries like Mexico face serious problems with respect to both, the literature exploring the links between the two remains limited. Studies of corruption rarely incorporate crime as a possible determinant or consequence or vice versa (for a review of the literature on corruption see Dimant 2013 and Triesman 2007; for a review of crime in general see Nueman and Berger 1988, Pratt and Cullen 2005, and Wilson 2013; for a review of crime in Mexico, see Widner, et al 2011). This theoretical lacuna is somewhat surprising given that the orthodox economics-based approach to corruption—which is often defined by reference to the law itself—borrows heavily from the rational choice logic (risk v. opportunities) informing the study of crime (Becker 1968; Rock 2009). To be sure, there are some exceptions to this, but this lack of attention leaves open a number of questions regarding the nature of the relationship linking corruption to crime, the direction of causality, and the issue of shared determinants – or, to reiterate, the relationship between a government and a people’s control of society and the state.

This paper explores the intersection of crime and corruption drawing on the Mexican case for examples and discussion.[1] Part one defines and differentiates the two key concepts. As defined here, the two concepts reach beyond conventional usage to encompass violations of the rule of law by citizens (crime) and state officials (corruption). Part two briefly explores the literature with a particular focus on the handful of empirical studies exploring the crime-corruption linkage. Concentrating solely in this paper on the issue of causality, part three then details how crime—under certain conditions—facilitates corruption and corruption nurtures crime both directly and indirectly by way of a set of intervening variables.[2] Building further on the model, I then highlight the common underlying determinants influencing both factors as well as examine the scope and reach of the model. I conclude this exercise by briefly laying out the next steps in the broader study of the interaction of state controls over society and societal controls over the state.

Concepts: Controlling Society/ Controlling the State

Crime is conceptualized here broadly to refer to violations of the law by members of society. As such, it reaches beyond criminal law to encompass violations of civil and regulatory law. Reflecting the complexity and scope of the law itself, crime in this context takes on many different forms, from blue-collar crime like robbery to white-collar violations of the commerce code, the labor code, health and safety laws, environmental regulations, etc. As such, violations can be differentiated along a wide range of criteria such as type (violent, non-violent, robbery, fraud, lack of compliance with building codes, tax fraud, drugs, ad infinitum), level of organization, motive, impact, etc. Disaggregating these types becomes important later in the analysis. Here it is important to note that regardless of specific type or classification, such violations of the rule of law by members of society fundamentally represent the failure of the state to effectively employ its “legitimate coercive power” to ensure security and protect those who have entrusted it to do so.[3]

Whereas the state is expected to mobilize its “legitimate monopoly of force” to control society, provide security, and hence curtail crime, in a general sense it is up to the institutions of the rule of law and democracy to limit or demarcate the state’s authority or, in short, to control state actors. As Francis Fukuyama (2014, 25) notes, these institutions “constrain the state’s power and ensure that it is used only in a controlled and consensual manner.” Whereas the rule of law limits what state officials can and cannot do in the exercise of their authority (it defines the “legitimate” part of the use of coercive power), democracy or the institutions of democratic accountability more specifically limit what the state can and cannot do with respect to certain individual rights (e.g. freedom of expression, freedom of assembly) and especially key governmental procedures (e.g. how to select political leaders and how to make public policy). While defining corruption is highly contentious, with definitions ranging from a specific type of behavior by public officials to those referring to much broader institutional norms, systemic failures, and structural formula,[4] it is broadly conceived here to encompass any such violations by state officials of the limits placed on their exercise of power. Just as crime represents illegal activity by members of society, corruption here represents the abuses of power by state officials broadly conceived (Morris 2014).

As used here then, corruption, like crime, is an exceedingly broad concept encompassing a wide range of activities arising from virtually every corner and crevice of the state’s political and administrative systems. This sweeping view of corruption parallels in many ways Green and Ward’s (2004) use of the concept “state crime.” [5] In addition to the more traditional forms of corruption (bribery, extortion, conflict of interest, nepotism, influence peddling), corruption here includes the abuse of human rights (torture, extrajudicial killings, disappearances), electoral fraud, obstructions of justice, etc.: all clear violations by state officials of the rule of law and democratic institutions for either personal or political gain.[6] As with crime, there are an assortment of ways to differentiate the many forms or classes of corruption (political versus administrative corruption, high-level versus low-level corruption, the particular state institution involved, abuse of human rights, electoral crimes, ad infinitum; see Morris 2011b), which again will become important later, but all reflect a fundamental violation by state officials of the basic principles and boundaries of the state’s authority.

Before considering the relationship between these two broad-based phenomena—abbreviated here to the concepts of crime and corruption—it is first important to acknowledge and dispense with some rather obvious tautological overhang. In most cases (not all, depending on the definition of corruption), corruption constitutes a crime. Indeed, the norms or standards establishing appropriate (i.e. noncorrupt) conduct for state officials—the authority that corruption is said to abuse—are normally spelled out in the written law. This fact obviously renders tautological the primary theoretical question about the relationship linking corruption and crime. To overcome this problem, I differentiate the acts by the actors involved since, even though corruption is a crime, it alone involves state officials and their use (or misuse) of state authority in the conduct of state affairs. Consequently, such acts are classified here as corruption, not crime. I take a similar approach when state officials engage in clearly criminal activities “off the clock” that are not traditionally considered corruption. This includes, for example, police operating an auto-theft or kidnapping ring, or the military illegally selling weapons or drugs. In such cases, of course, crime and corruption become almost indistinguishable. This is a particular problem in Mexico, of course. [7] Even though such acts may be prosecuted as crime and officials may face criminal charges, I consider these sorts of acts under the heading of corruption since again it involves some form of the abuse of authority. This approach is similar to the one adopted in the study by Center for the Study of Democracy, Sofia (2010) looking at the link between organized crime and corruption. On the other side of the equation, but in a similar manner, the offering of a bribe to a public official by a citizen also constitutes a crime. To avoid this problem, I do not consider the part of corruption involving the citizen to be a crime per se or corruption.[8]

Literature Review

The literature on corruption and crime rarely intersect. Eugene Dimant’s (2013, table 1) near exhaustive summary of works focusing on the causes of corruption, for instance, lists forty determinants, none of which refer to crime. Many corruption studies incorporate, and even emphasize, the concept of the rule of law, and while some measures of rule of law include crime and respect for the law within society (see Merkel 2012), most studies tend to characterize rule of law as the effectiveness of the judicial and criminal justice systems (characteristics of the state, not society) or the extent to which the state and state officials abide by the law and the limits on state power (see O’Donnell 2004; Tamanaha 2004). Such conceptualizations, however, seem rather close to definitions of corruption, thus raising the issue of tautology (see Beyerle 2011).[9] Indeed, in such studies the rule of law seems almost synonymous with effective anticorruption (Mungiu-Pippidi, 2013).[10] Similarly, the analysis of crime also rarely seems to incorporate a concern for corruption. The most recent edition of James Q. Wilson's (2013) text Thinking about Crime, for instance, contains just one index reference to corruption, noting the perception that heroin use may lead to more police corruption (p. 183). Robert Agnew's (2005) general theory on crime similarly does not include corruption as an explanatory variable, focusing instead, as do most works on crime, on such factors as personality traits, family, school, peers, and work of the individual.

There are some important exceptions to this pattern, of course (e.g. Buscaglia and Van Dijk 2003; Yankah 2013; Uslaner 2008). The literature on organized crime in particular stresses how drug trafficking organizations cannot exist without corruption (see for instance Buscaglia and Van Dijk 2003; Buscaglia 2011 and Van Dijk 2007; Center for the Study of Democracy 2010; Collins 2011; Hung-En Sung 2004; O’Day and López 2001; Hanson 2008; Shelley 2005), a view that dominates popular and political rhetoric. Mexican President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) captured this sentiment during a meeting of the National Council of Public Security in 2008: “Crime cannot be understood without the protection of impunity and corruption of the police” (author translation) (Milenio August 27, 2008). While some cast crime as the causal agent influencing corruption and others see corruption as nurturing violence and instability (Human Rights Watch 2007 and Le Billon 2003, both cited in Beyerle 2011), many characterize the relationship as reciprocal. John Bailey’s (2014, 9) model of Mexico’s “security trap,” for instance, ties crime, violence, corruption and impunity together in a mutually reinforcing manner, trapping the country in a state of low-level equilibrium.

Beyond the literature on organized crime, some empirical studies explore the relationship, though such studies tend to speak more to correlation than to causation. In one such study focusing on the impact of organized crime, rule of law and corruption on national wealth, Jan Van Dijk (2007) uncovers a strong correlation linking a composite measure of organized crime to perceived levels of corruption, a finding that seems to substantiate the writings and conventional wisdom associating organized crime with corruption. Interestingly, however, he uses grand corruption as part of the composite measure of organized crime, thus raising the issue of partial endogeneity. Of equal importance, Van Dijk (2007) fails to find any correlation linking perceived corruption to selected measures of common crime. Other empirical studies also point to links between certain types of crime and certain measures of corruption. Cross-national studies by Dutta et al (2011) and Schneider and Buehn (2009), for example, find a correlation linking the size of the informal economy to level of perceived corruption, a finding that supports Bailey’s (2014, 43) assertion tying Mexico’s informal economy to corruption. Focusing only on European states, the Center for the Study of Democracy, Sofia (2010, 331) uncovered a strong correlation linking corruption to both organized crime and the informal (or grey) economy. Roh and Lee (2013), in turn, find an inverse relationship linking a composite measure of social capital—an indicator that includes a survey question on the respondent’s “willingness to accept a bribe”—to robbery (though not burglary) at both the country and individual level of analysis. Extending outward a bit further, Hunt (2004) links crime to corruption by showing that people are more likely to engage in petty corruption if they have been the victim of a fraud, robbery or assault (cited in Uslaner 2008, 80). Playing even further on perceptions, Dammert and Malone’s (2002) study on Argentina finds a correlation linking high levels of perceived corruption to a lack of confidence in the police and fear of crime: factors clearly tied to crime. Eric Uslaner (2008, 82) also finds a correlation linking perceived malfeasance at the top (corruption) to the perceived extent of pickpocketing within society. Uslaner, however, seems to reverse the causal arrow found in the literature on organized crime, concluding that “corruption leads to more crime,” not the other way around (Uslaner 2008, 17). Finally, with a focus on Mexico’s thirty-one states and the federal district from 2007 to 2010, I (Morris 2013) found a correlation between the level of perceived corruption and the perception of insecurity. Such cross-state comparisons reveal that states at the forefront of the war on organized crime during these years and suffering the highest levels of violence exhibited slightly higher levels of insecurity and corruption (Morris 2013).

Linking Crime and Corruption

At the broadest level, there should be no a priori reason to expect a relationship linking crime and corruption. However, numerous scenarios and specific cases suggest that the two not only often go hand in hand, but that under certain conditions crime facilitates corruption and vice versa. This section presents the rough contours of a model mapping the linkages based on a discussion of competing claims regarding the direction of causality,[11] direct and indirect linkages, shared determinants, and the issue of mutual causality. It concludes by stepping back to specify certain conditions and limitations in the model. The discussion draws on the current literature generally and Mexico specifically.

Crime -> corruption (Society to state)

Crime causes corruption. The one area in the literature pointing to and specifying a clear and direct causal link running from crime to corruption centers on organized crime, as noted. The seemingly strong consensus not only holds that organized crime cannot operate without corruption and that the two are intricately and inherently linked, but that organized crime corrupts state officials (see, for instance, Andreas 1998; Beittel 2011; Hanson 2008; Naylor 2003, 2009; O’Day and López 2001; O’Day 2001; Pimental 2003; Shelley 2005). The 1967 U.S. Task Force Report on Organized Crime was explicit in its causal logic: “all available data indicate that organized crime flourishes only where it has corrupted public officials” (cited in Kelly 2003, 128-129). In Mexico, of course, many analysts have long agreed with this viewpoint (see Lupsha 1995). As Laurie Freeman (2006, 12) notes, “Doing business entails bribing and intimidating public officials and law enforcement and judicial agents . . . organized crime cannot survive without corruption, and it looks for opportunities to create and deepen corruption.”

Certainly no one would suggest that only organized crime accounts for the nation’s corruption; still, organized crime is seen as having a corrupting influence. Through the payment of bribes to police, ministerios públicos, judicial institutions, mayors, customs officials, and others, organized crime gains important tools for the operation of their illicit enterprises, such as nonenforcement of the law (state acquiescence), information on the operations of police or rival criminal organizations, hiring and promotion decisions within state agencies, procurement decisions, logistical support, etc. For organized crime, corruption thus represents a means—apparently a necessary means—of conducting business and is generally considered preferable to violently confronting the state, though a second-best solution to simply avoiding it (Bailey and Taylor 2009). This mode of corruption represents, in turn, a form of state capture. The societal organization (criminal organization) uses illegal payoffs to divert the behavior of state officials away from that authorized by and for the institution and toward the objectives of the societal organization. Like a perverse form of privatization, organized crime uses extensive payoffs to state officials to capture police and other state officials.

Examples from Mexico are sadly abundant. Starting at the top, in 1997, the head of Mexico’s drug enforcement agency, General Jorge de Jesús Gutiérrez Rebollo, was jailed for collaborating with Amado Carrillo Fuentes of the Juarez cartel. In 2008, the government’s Operación Limpieza allegedly uncovered payments, some as high as US $450,000 a month, to over thirty officials of SIEDO (Subprocuraduria de Investigacion Especializada en Delincuencia Organizada)—the agency in charge of fighting organized crime—in return for providing confidential information to the Sinaloa cartel on law enforcement operations, including those of the US Drug Enforcement Administration (Latin American Mexico & NAFTA Report, November 2008; Padgett 2008). Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman Loera’s infamous escape from El Puente prison in Jalisco in 2001 revealed extensive payoffs to dozens of prison officials.[12] The former governor of Quintana Roo, Mario Villanueva Madrid, was convicted and imprisoned in both Mexico and the US for laundering money for the Juarez cartel. It is alleged that the governor received from $400 to 500,000 for each shipment that went through his state. In 2009, the infamous Michoacanazo featured the arrest (and subsequent exoneration) of over thirty local officials in the western state of Michoacán, all for alleged links to drug traffickers. Indeed, bribery and the “partial privatization” of police and state officials are perhaps most evident at the local level. Edgardo Buscaglia (cited in “Organized Crime Highlights Corruption…” 2011), for instance, estimates that in 2010, 72 percent of Mexican municipalities had “stable, open and notorious” organized crime presence, where the authorities “at some level” were protecting these groups. Though the outcome may be largely the same, such relationships often blur the line between corruption and intimidation. One report, for example, noted that in twelve municipalities in the state of Mexico, organized crime operated protection rackets not only with businesses, but with local and federal deputies who remained quiet because the criminal groups had them “identified and threatened” to harm their families (Milenio 10/6/2008) (see also Lacey 2008).

But while this causal narrative makes sense for organized crime, it seems somewhat less clear with respect to other forms of crime. Though Jorge Castañeda (2011, 181) contends that in Mexico “lawlessness breeds corruption,” it remains difficult to imagine how everyday blue-collar street crimes such as robbery or even white-collar office crimes committed by individuals might directly promote corruption.[13] For most crimes, evasion is the primary strategy and dominant mode of operation. Even so, there are many other crimes that might lead directly to corruption. Just like drug trafficking organizations seem to require corruption to operate, so too might various forms of fraud and illegality within society that are not commonly associated with organized crime or with street crime. Those involved in the informal economy, for instance, often have to bribe local officials to acquire “permission” to operate (Bailey 2014, 43). Payoffs to customs officials and others facilitate the introduction of contraband into the country. The operation of fake or unauthorized taxis often entails bribing key officials or quotas to party leaders.[14] The ability of businesses to “disobey” everything from building to labor codes or escape taxes often seems to require corrupt payoffs to inspectors and other officials. Generally, it seems that the common denominators here involve more organized, ongoing criminal activities that are difficult to hide from the state rather than more individual, nonorganized, intermittent activities that are more successfully concealed from state enforcers. Given that evasion is likely the priority, only when such evasion becomes less practical is bribery or corruption more likely to occur (Bailey and Taylor 2009).

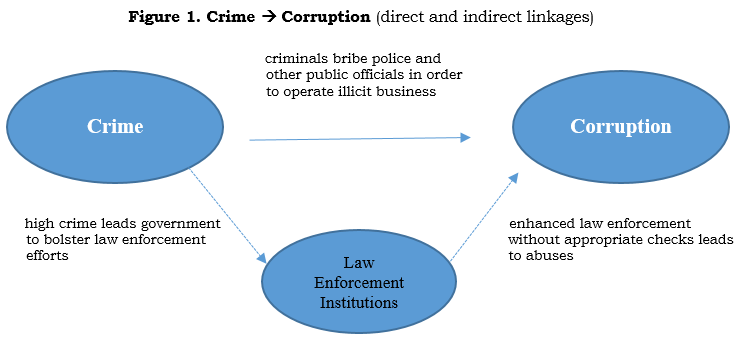

Beyond this direct link, crime may also lead to corruption indirectly as a result of the state’s reaction to crime (figure 1). At a macro level, greater real or perceived crime and the related social disorder and instability bolsters the need for the state to crack down on crime and establish order. This emphasis on security leads those in government, often with the public’s support (Malone 2013), to launch mano dura policies that in turn empower law enforcement while simultaneously weakening the constraints and checks on state agencies, thus increasing the likelihood of corruption and abuse of authority. This scenario plays out in a number of ways. First, as ends come to justify means, state officials increasingly engage in illegal activities (considered here as forms of corruption) such as torture, illegal detentions, forced disappearances and even extrajudicial killings all in the fight to “restore” order. Second, the rapid mobilization of state resources to battle crime and establish “law and order” expand the opportunities for abuse and corruption. Mexico’s deployment of the military to fight drug trafficking organizations, which dates back a number of years but began in earnest under President Calderón, significantly expanded the military and police’s exposure to corruption and abuses, resulting in a dramatic increase in allegations of human rights abuses, forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, and corruption.[15] Third, in a rather perverse way, increased enforcement threatens the operation of illegal activities and thus enhances their propensity to and reliance on bribery to operate. Edgardo Buscaglia (2008) refers to the “paradox” that comes from cracking down on drug trafficking: the more the government bears down on traffickers through the justice system, the more likely they are to corrupt and employ additional violence. Finally, in an even more round-about and indirect manner, high levels of crime raise personal feelings of insecurity and undermine trust in society and the legitimacy of democratic institutions, as Karstedt and LaFree (2006, 9) point out, raising at least the perception of increased corruption.[16]

Corruption -> crime (State to society)

As Peter Andreas (1998, 161) notes, corruption is a two-way street and “involves not only the penetration of the state, but also penetration by the state.” Flipping the causal model around captures Uslaner’s (2008, 17) proposition that “corruption leads to more crime.” While the prior causal equation relates to a specific class of crime (organized), this causal narrative tends to encompass a broader view of crime, and, like the prior model, occurs through both direct and, more importantly perhaps, indirect mechanisms.

The direct causal relationship finds corrupt public officials promoting or encouraging criminal activities by members of society. This includes the complex schemes orchestrated by public officials (via conflict of interest, graft, fraud, etc.) that include associated crimes of civilian allies (again, beyond the crime of bribery), the coordination and operation of drug-trafficking operations under the direction of corrupt state officials, the laundering of ill-gotten funds through front businesses or banks on behalf of state officials, or even the operation of an auto-theft ring by police. In contrast to the state capture model seen earlier, this causal scenario represents a form of societal capture, as Andreas notes, with individuals or businesses convinced or compelled by payoffs, profits or the abuse of authority by corrupt officials to engage in criminal acts. Of course, the fact that state officials vested with authority are involved eases the way for civilians since it provides a certain degree of cover and lessens their likelihood of being caught and punished for their crimes.

Disentangling cause and effect here is admittedly difficult. Before exploring the more indirect links whereby corruption causes crime, a brief historical detour into Mexico helps to crystallize the distinction here between these two causal equations. A large body of literature on Mexico contends that for years during the decades-long PRI-gobierno drug traffickers operated under a single hierarchy with public officials controlling, extorting from, and protecting their operations, a narrative that positions corruption as the independent variable nurturing criminal enterprises (see, for instance, Andreas 1998; Astorga and Shirk 2010; Flores 2009; Lupsha 1995; Shelley 2001; Shirk 2010). As Peter Lupsha (1995) contends, “key traffickers and trafficking routes in a centralized authoritarian system like Mexico always needed the ‘con permiso’ of those within the Federal District.” The powerful PRI-led state enforced the norms of operations on and among the various trafficking groups. Under the prevailing “rules of the game,” as George Grayon (2010, 29) contends, the authorities “allocated ‘plazas’” and “drug dealers behaved discretely, [and] showed deference to public figures.” When conflict among organizations emerged, state governors, under the direction of central authorities, stepped in to resolve it. This historic narrative, in sum, illustrates the corruption -> crime model.

Political changes in Mexico and in the industry itself in the twenty-first century ushered in a deterioration of the state’s control over drug trafficking organizations, however, and altered the direction of the causal equation, shifting Mexico away from the corruption -> crime model toward one in which crime -> corruption. The rise of political competition, the end of PRI’s grip at the state and national levels, and even democratization and liberalization in Mexico undermined the prevailing patterns of corruption by hampering PRI’s capacity to control the enforcement and nonenforcement of the law (Morris 2009; Snyder and Duran-Martínez 2009, 262). As opposition parties began to capture ever greater control of state and local governments and, by 2000, the presidency, the number of potential protectors grew, thereby undermining the ability of a centralized state to guarantee its side of a corrupt bargain. In short, as local power increasingly fell outside the PRI-controlled networks, federal agents, local police, and corrupt officials all began to act more autonomously (Grayson 2010, 31). With upper-level officials now unable to fully control lower-level officials, according to Vidriana Rios (2011), political decentralization altered corruption from a single-agent game to a multiple-agent game affecting the price of bribes, government’s incentives to enforce the law, and the level of political violence. In effect, this shifted the causal equation with ever more powerful drug trafficking organizations not only escaping state control, but increasingly colonizing and capturing various state entities for their own purposes. This significantly altered the impact of drug trafficking and corruption in the country.[17]

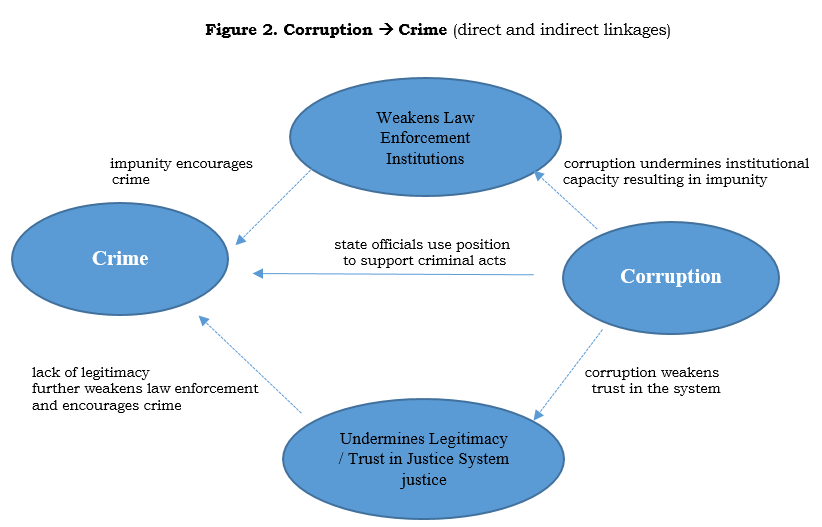

Returning to the discussion linking corruption to crime and looking beyond the direct links tying corruption to crime, corruption also arguably plays an even more critical role in facilitating crime indirectly by creating the conditions conducive to crime (see figure 2). The literature here points to two broad-based intervening factors: institutional effectiveness and legitimacy. First, corruption facilitates crime by undermining the capacity of state institutions (law enforcement and the judiciary in particular) to deter crime. Reflected by high rates of impunity, weak institutions, according to the standard economic theory of crime (Becker 1968), lessen the likelihood of being caught and punished for committing a crime, thereby encouraging criminal activity (LaFree 1998, cited in Aguierre and Amador Herrera 2013, 223). Over a decade ago, Guillermo Zepeda (2004) calculated Mexico’s rate of impunity at a staggering 97 percent. In 2013, Mexico’s statistical agency INEGI, put the calculation at 94 percent (Zúñiga 2014). To be sure, corruption is not the sole source of the failure of the police or the entire justice system to investigate, arrest, and successfully prosecute criminals. Corruption shares blame with other aspects of weak institutions like outside political manipulation and the lack of resources, training, autonomy, oversight, , and public support. Still, corruption plays an important role in crippling the effectiveness of these institutions and distorting their operation. According to Luis Rubio (2015, 81), “Mexico’s problem is not the criminality or the violence, but the absence of the government, the absence of competent governmental institutions capable of maintaining order, imposing rules, and earning the respect of the citizenry” (Rubio 2015, 81).

Even beyond this impact based on the assumed rational calculations of criminals, the failure of law enforcement to protect individuals or the judiciary to protect people’s property or rights also tends to promote another sort of illegal activity. It prompts citizens to engage in illegal acts themselves to protect their own interests or pursue justice. This includes illegal acts by citizens associated with vigilante justice or similar actions designed to exact justice. If the state is incapable of providing security or resolving conflict within society, individuals and perhaps organization often feel forced to pursue their own justice, violating the law in the process. While vigilantism has a long history in Mexico, recent years have seen a spike in the number and scope of community self-defense groups, particularly in the states of Guerrero and Michoacán (on vigilantism in Mexico see Zizumbo-Colunga 2010, and Hinton and Montalvo 2014).

A second intermediate factor linking corruption to crime is the lack of trust and legitimacy in the institutions of the state, particularly those related to the justice system, including the lack of trust in the law itself. Alongside Mexico’s staggering impunity rate resides a deep distrust of the police and the judiciary as well as the expectation of corruption, all products of real and perceived levels of corruption in the country. This lack of trust and legitimacy encourages crime in a number of ways. First, it prevents the public from cooperating with the fight against crime, a critical if not indispensable tool in the state’s ability to fight crime. In fact, as much as 60 percent of Mexico’s high impunity rate noted earlier stems from the public’s failure to report crime, owing to the lack of trust in and even fear of the police (Zúñiga 2014).[18] At a broader level as well, the lack of trust in state institutions and the law carries a cultural effect, promoting disrespect for the law (Anderson and Tverdova 2003). As Bailey (2014, 21) contends, “weak trust and confidence in the police and judiciary reinforce a civic culture of alegality, which, in turn, creates a context that tolerates illegality.” This goes beyond trust in the police and judiciary, however, and connects to the legitimacy of the government and the law itself. The public’s disillusionment in the law, law enforcement, and the state, particularly the perception that the law favors the rich, powerful, and the connected, undermines obedience to the law (Yankah 2013, 63).

In many ways, there is an imitation effect involved: if the public believes that state officials are not bound by the law, then the public hardly feels compelled to adhere to the law either. When citizens regard the law as a tool manipulated by those in power for their own benefit, such vices “can make it clear to citizens that the law does not take them seriously as agents and is to be manipulated for personal gain, draining the legitimacy, the very lifeblood, from a system” (Yankah 2013, 63). As Rubio (2015, 18) points out, “No one feels obliged to comply with the law, above all when he observes that many others do not do so and even in the worst of circumstances application of the law can always be ‘negotiated.’” This point underlies Uslaner’s (2008, 59) assertion that “malfeasance at the top encourages street crime more than delinquency promotes dishonesty at the top.”

Such views pervade Mexico. The 2012 National Survey of Political Culture, for example, finds substantial majorities agreeing that public officials are unconcerned about people like themselves (75.5 percent), and that when laws are made the politicians take into account either the interests of the political parties or their own personal interests (67.4 percent) rather than those of the people (ENCUP 2012). When asked who violates the law the most, 37.5 percent of respondents to Transparencia Mexicana’s 2005 National Survey of Corruption and Good Government cited as their top response “politicians,” with another 15.2 percent pointing to the police, and 14.2 percent to government workers (66.9 percent combined), while just 8.0 percent to citizens. When asked how much government officials abide by the law, not only did 73.3 percent select the response “a little,” but more chose the response “none” (17.2 percent) than “a lot” (9.5 percent). Such views clearly sustain the low levels of confidence historically found in Mexico’s public institutions. Indeed, in the 2011 National Survey of Constitutional Culture 79.6 percent of respondents felt that the people are insufficiently protected against the abuse of authority.

A final indirect effect parallels the impact of the state’s efforts to address crime, noted earlier. Cracking down this time on corruption can have a perverse and unexpected effect on crime. As Vanda Felbab-Brrown (2011, 38) contends, the government’s efforts to reduce corruption and tackle high criminality in its law enforcement bodies has led to more insecurity, making existing corruption networks more “murky” (cited in Tromme and Lara Otaola 2014, 574). One concern is that the firing of corrupt police or police who fail confidence control evaluations leads to an uptick in crime as the former police join the ranks of organized crime or use their unique training and skills in the “private sector” in criminal activities. In a sort of revolving door operation, many former police and military officers in Mexico have gone on to pursue careers with DTOs, including the infamous and violent Zetas drawn largely from the ranks of the special forces of the Mexican military (Grayson 2008, 2010).

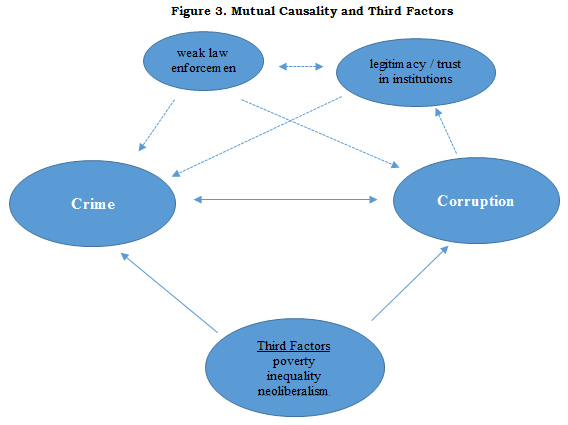

Mutual Causality and Third Factors

To the extent the literature addresses the crime-corruption relationship, much of it suggests a mutual, reciprocal, causal relationship linking the two. This broader causal model rests largely on a fusion of the two equations just outlined and is rather straightforward. Whether one starts the explanation with corruption encouraging criminal activity or criminals corrupting state officials, the point is that both occur simultaneously and that both undermine the state’s enforcement capabilities and weaken trust and legitimacy, thus setting the stage for more crime and more corruption. The result is a state of low-level equilibrium or what Bailey (2014) describes as a security trap.

An important dimension of a mutual causal relationship is the existence of shared causal agents. Such shared determinants, of course, could also be part of a spurious relationship between crime and corruption. Many such third factors relate to the indirect factors cited earlier, but extend further out as factors directly affecting both variables (see figure 3). Weak law enforcement institutions, for example, not only nurture crime by reducing the likelihood of being caught and punished, as indicated, but they also feed corruption by reducing the risk of being caught and punished for corrupt acts (Buscaglia and Van Dijk 2003). Just as Mexico fails to prosecute those committing common crimes, few officials are ever prosecuted for corruption, the abuse of human rights, or other state crimes. The responsibility to deter the “crime” of corruption falls on a different set of institutions than those fighting crime, a point returned to momentarily, but in Mexico the institutions of accountability are arguably weaker than the weak institutions focused on fighting crime. Though many bureaucrats in Mexico receive minor administrative sanctions through the SFP, officials are rarely investigated and prosecuted. Part of this institutional weakness stems from the lack of cooperation between police, the PGR, and the SFP (Tromme and Lara Otaola 2014, 573); part of it is the lack of political will. Not only are few police or military personnel prosecuted for corruption or violating human rights, but the reports and recommendations of both the ASF (Auditoria Superior de la Federación) and the CNDH (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos) often go unattended.

In addition to sharing the institutions of justice and legitimacy, other “third” factors also play a role in shaping both crime and corruption in a similar direction. Poverty, inequality, and the policies of neoliberalism, in particular, have been shown to increase both crime and corruption rates. The meta-analysis of over 200 quantitative studies by Pratt and Cullen (2005; cited in Fox and Hoelscher 2012), for example, reveals the important role of poverty and inequality in influencing crime rates. In Mexico these factors have helped set the stage for the growth of organized crime and the dramatic rise of violence in recent years. According to Abello-Colak and Guarneros-Meza (2014), the growth of poverty and inequality stemming in part from the policies of neoliberalism facilitated the expansion of drug trafficking organizations since they provided the poor with an opportunity for upward mobility and security. Such factors also led to the expansion of the informal economy along with its accompanying corruption (Coronado 2008; Pansters 2012). At the same time, these factors (poverty, low levels of economic development, inequality, and the policies of neoliberalism) have also been linked to heightened levels of both real and perceived corruption (see Bayart 1993, cited in de Maria 2008; Coronado 2008; Sandoval 2013; Uslaner 2008; Uslaner and Rothstein 2013; Xin and Rudel 2004). As demonstrated most clearly by Uslaner (2008) and You and Khagram (2005), inequality not only plays a critical role in determining the levels of corruption, but in mutual causal fashion, corruption also serves to maintain or even worsen the level of inequality by further rewarding the rich, the powerful and the connected.

Limitations, Specifications, and More Questions

The positive associations just described, whether unidirectional or bidirectional, direct or indirect, seem to fit the Mexican case. Yet it is important to make clear the limitations or specifications incorporated into the model. When viewed from a different angle, crime and corruption can be seen as inversely (rather than positively) related or totally unrelated. To reiterate, Van Dijk’s (2007) cross-national study failed to show a significant correlation linking crime and corruption. Such specification involves disaggregating the two key concepts and the different state institutions involved as well as taking into account the external determinants that crime and corruption do not share, taking a step or two down on the ladder of abstraction.

First, it is important to emphasize that the arguments tying corruption to crime and vice versa relate to rather specific arenas and types of crime and even types of corruption. Among other things, this means that while the two may interact and influence each other, they may account for only part of the variation or explanation. Crime (and primarily a certain class of crime) is one of many variables shaping corruption and only may affect certain classes of corruption (police, military, prosecutorial, judiciary, local, etc.). Corruption, similarly, may have a limited and specified effect on crime and, again, be one of many factors shaping crime. Corruption-induced impunity may encourage some to engage in illegal activities just as the lack of faith in the justice system may prompt some to take the law into their own hands, but most citizens prefer to abide by the law despite the prospects of impunity. As noted, much of the literature and argument linking crime and corruption relates to organized crime. This initial point represents quite simply the “warning label” attached to all probability equations.

It is also important to differentiate among state institutions involved in crime and corruption. Though considered part and parcel of a country’s justice system, the specific institutions and agencies focusing on criminal activity are not the same ones targeting corruption. In Mexico, for example, corruption broadly conceived is handled (to the extent it is handled) by a range of institutions including the SFP and their embedded internal auditors throughout the federal bureaucracy, the ASF, the CNDH, the IFAI (Instituto Federal de Aceso a la Información), INE (Instituto Nacional Electoral), the Honor and Justice Commissions within police departments, and the specialized labor review boards and administrative courts. It is only the PGR (Procuraduría General de la República), however, that can prosecute officials for corruption (for overviews on police corruption in Mexico see Davis 2006; Fondevila 2008; Sabet 2010; and Uildriks 2009). Despite some overlap, particularly at the prosecutorial and judicial levels, these agencies and personnel are not the same as those devoted to preventing, investigating, prosecuting and adjudicating crimes. While there may be reasons to believe that if there is corruption and inefficiency in one area or arena, a similar degree of corruption and inefficiency will reign in others, this differentiation makes it possible that, theoretically at least, some institutions may perform far better than others. If we disaggregate, it is possible then to have within the same state the coexistence of weak/ineffective/corrupt institutions alongside stronger/effective/noncorrupt institutions. By differentiating among state institutions, it thus becomes possible to envision a situation where state control over society is strong and repressive so as to maintain a low crime rate, but where accountability structures binding state officials to the rule of law are weak or vice versa. Indeed, Fukuyama (2014) highlights a number of countries where state strength is high and yet there are few controls on the state, resulting in high levels of corruption.[19] Daniel Kaufmann (2010) points to the opposite phenomenon to support his conclusion that corruption and crime in fact are unrelated, citing the case of Chile where corruption is low and yet the crime rate remains high. These are all empirical questions.

This differentiation of state institutions, moreover, is critical when coupled with the earlier point regarding the tendency for state officials and even the public to prioritize the fight against crime and violence—and the need for security and political stability—over fighting corruption. Viewed from this perspective, any sort of success in fighting crime would likely result in an apparent inverse relationship: a decrease in crime coupled with an increase in corruption and abuse of authority owing to the state’s anticrime fighting strategy. In short, corruption is often cast as a problem of secondary importance, a residual of the unintended consequences of more important policy concerns.[20]

Finally, and expanding further on this last point differentiating institutions, it is important to recognize that while crime and corruption may share certain determinants, there are many they do not share. The literature review presented earlier largely supports this notion. Most studies of corruption point to institutional variables as primary causal agents, while others focus on such societal factors as tolerance and related cultural variables. Meanwhile, the predominant approach to the study of crime tends to focus on a different set of variables reflecting socioeconomic and even psychological phenomena of the individual. Indeed, it is the lack of shared determinants that leads Kaufmann (2010) to claim that crime and corruption do not always coexist. Even inside each factor, different classes of crime and different types of corruption stem from unique factors. Analyses of homicide and property crimes, for instance, show they are not caused by the same factors (Nueman and Berger 1988). Similarly, despite studies pointing to certain linkages between the two, the factors behind police corruption or low-level bureaucratic corruption are largely unrelated to those determining high-level political corruption (see Lofti 2014 and Uslaner 2008). Clearly, more work is needed in exploring these interrelationships between the various forms and classes of corruption.

Conclusion

The purpose of this essay has been to explore the relationship between corruption and crime. The exploration has been largely theoretical, drawing on secondary sources with examples and illustrations from contemporary Mexico. The model developed here points to a complex interplay of causal agents, resulting in both direct and indirect linkages moving in both directions, and hence the underpinnings of the low-level equilibrium model crafted by Bailey (2014). The model shows that corruption is one among many factors that exacerbate crime and that crime is one of many factors influencing corruption. Such models, moreover, suggest that efforts to attack crime, which tends to receive priority attention, are not only handicapped by corruption, but may make corruption worse, as seen in the case of Mexico. Similarly, attacking corruption without fighting crime may produce limited results or even make matters worse.

This review, as noted, is part of a much larger study exploring the relationship between a government and a people’s control of society and the state. This broader project brings into focus the interplay between efforts to empower the state (in order to control society), while constraining it (in order to control the state) and those that seek to empower society (in order to control the state), while constraining it (in order to control society). This interwoven process of empowering and yet constraining society and state encompasses both various institutional agents and the ideological narratives and discourses that support the state’s institutions and policies, as well as the public’s attitudes, expectations, and metrics used to determine appropriate (i.e. noncorrupt) behavior, the contours of legitimacy, and thus the limits on power (state) and freedom (society). Using Madison’s pithy comment in Federalist Papers #51, “In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself,” the broader project seeks to understand the state and societal mechanisms used to “oblige” the government to control itself (anticorruption), the extent to which this is tied to (facilitated by or undermined by) the government’s ability to “control the governed,” and whether it (the government) can indeed accomplish the first task without attending to the second task. Understanding the relationship linking crime, which is part of the government’s control “of the governed,” and corruption, which represents controls over “itself,” is but one dimension of this broader line of inquiry.

References

Abello-Colak, Alexandra and Valeria Guarneros-Meza. 2014. “The Role of Criminal Actors in Local Governance.” Urban Studies 51 (15): 3268–3289.

Agnew, Robert. 2005. Why Do Criminals Offend? A General Theory of Crime and Delinquency. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Aguirre, Jerjes and Hugo Amador Herrera. 2013. “Institutional weakness and organized crime in Mexico: The Case of Michoacan.” Trends in Organized Crime 16: 221–228.

Anderson, Christopher J., Yuliya V. Tverdova. 2003. “Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes toward Government in Contemporary Democracies” American Journal of Political Science 47 (1): 91–210.

Andreas, Peter. 1998. “The Political Economy of Narco-Corruption in Mexico.” Current History April: 160–165.

Astorga, Luis and David A. Shirk. 2010. Drug Trafficking Organizations and Counter-Drug Strategies in the U.S.-Mexican Context. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Mexico Institute, Working Paper Series on U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation, April.

Bailey, John. 2014. The Politics of Crime in Mexico: Democratic Governance in a Security Trap. Boulder, CO: First Forum Press.

-------- 2009. “Corruption and Democratic Governability in Latin America: Toward a Map of Types, Arenas, Perceptions, and Linkages.” In Corruption and Democracy in Latin America, edited by Charles H. Blake and Stephen D. Morris, 83–109. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Bailey, John and Matthew M. Taylor. 2009. “Evade, Corrupt, or Confront? Organized Crime and the State in Brazil and Mexico.” Journal of Politics in Latin America 2: 3–29.

Bateson, Regina. 2010. “Does Crime Undermine Public Support for Democracy? Findings from the Case of Mexico.” Unpublished.

Bayart, J. F. 1993. The State in Africa. The Politics of the Belly. London: Longman.

Becker, G. 1968. “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 76: 169–217.

Beittel, June S. 2011. Mexico’s Drug Trafficking Organizations: Source and Scope of the Rising Violence. Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report for Congress, 7–7500 (June 7).

Beyerle, Shaazka. 2011. “Civil Resistance and the Corruption-Violence Nexus.” Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 38 (2): 53–77.

Booth, John A. and Mitchell A. Seligson. 2009. The Legitimacy Puzzle in Latin America: Political Support and Democracy in Eight Nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buscaglia, Edgardo and Jan Van Dijk. 2003. “Controlling Organized Crime and Corruption in the Public Sector.” Forum on Crime & Society 3 (1 and 2): 3–34.

Buscaglia, Edgardo. 2008. “The Paradox of Expected Punishment: Legal and Economic Factors Determining Success and Failure in the Fight against Organized Crime.” Review of Law & Economics 4 (1): 290–317.

Carrasco Araizaga, Jorge. 2015. “’Gates’: permiso para secuestrar.” Proceso 1996 (1 de febrero): 28–31.

Castañeda, Jorge. 2011. Mañana Forever? Mexico and the Mexicans. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Catterberg, Gabriela and Alejandro Moreno. 2006. “The Individual Bases of Political Trust: Trends in New and Established Democracies.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 18 (1): 31–48.

Celaya Pacheco, Fernando. 2009. “Narcofearance: How has Nacoterrorism Settled in Mexico?” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 32: 1021–1048.

Center for the Study of Democracy, Sofia. 2010. “Examining the Links between Organized Crime and Corruption” (excerpt) Trends in Organized Crime 13: 326–359.

Collins, Randall. 2011. “Patrimonial Alliances and Failures of State Penetration: A Historical Dynamic of Crime, Corruption, Gangs, and Mafias.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 636 (1): 16–31.

Coronado, Gabriela. 2008. “Discourses of Anti-corruption in Mexico: Culture of Corruption or Corruption of Culture?” Portal Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies 5 (1): 1–23.

“Corrupción en México, un problema cultural: Peña Nieto.” 2014. El Economista, September 8 Accessed November 25, 2014. http://eleconomista.com.mx/sociedad/2014/09/08/corrupcion-mexico-problema-cultural-pena-nieto

Dammert, Lucia and Mary Fran T. Malone. 2002. “Inseguridad y temor en la Argentina: El impacto de la confianza en la policía y la corrupción sobre la percepción ciudadana del crimen.” Desarrollo Económico 42 (166): 285–301.

Davis, Diane E. 2006. “Undermining Rule of Law: Democratization and the Dark Side of Police Reform in Mexico” Latin American Politics and Society 48 (1): 55–86.

Dimant, Eugen. 2013. “The Nature of Corruption: An Interdisciplinary Perspective.” Economics Discussion Paper No. 2013-59. Accessed January 20, 2014. http://www.economics-ejournal/discussionpapers/2013-59.

Dutta, Nabamith, Saibal lKar,and Sanjukta Roy. 2011. “Informal Sector and Corruption: An Empirical Investigation for India.” Discussion Paper No. 5579, Institute for the Study of Labor (Bonn), March.

Encuesta Nacional de Corrupción y Buen Gobierno. 2001, 2005, 2010. Mexico City: Transparencia Mexicana (Results available at www.transparenciamexicana.org.mx. Accessed November 24, 2013).

Encuesta Nacional de Cultural Constitucional: Legalidad, Legitimidad de las instituciones y rediseño del Estado. 2011. Mexico, DF: IFE- IIJ, UNAM.

Encuesta Nacional de la Cultura Política. 2012. Mexico City: Secretaría de Gobernación (Results available at http://www.encup.gob.mx/encup. Accessed November 24, 2013).

Escalante Gonzalbo, Fernando. 2009. “Homidicios 1990-2007.” Nexos, September: 25–31.

Felbab-Brown, Vanda. 2011. Calderon’s Lessons from Mexico’s Battle against Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking in Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, and Michoacán. Washington: The Brookings Institution.

Flores, Carlos. 2009. “Drug Trafficking, Violence, Corruption and Democracy in Mexico.” November. Accessed May 15, 2011. http://www.norlarnet.uio.no/pdf/news/announcements/conference_2009_presentations/carlos_flores_presentation.pdf.

Fondevila, Gustavo. 2008. “Police Efficiency and Management: Citizen Confidence and Satisfaction.” Mexican Law Review 1 (1): 109–118.

Fox, Sean and Kristian Hoelscher. 2012. “Political Order, Development and Social Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 49 (3): 431–444.

Freeman, Laurie. 2006. “State of Siege: Drug-Related Violence and Corruption in Mexico.” WOLA Special Report, Washington Office on Latin America, June.

Fukuyama, Francis. 2014. Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Ganesan, A. 2007. “Human Rights and Corruption: The Linkages.” Human Rights Watch. Accessed November 30, 2013. http://hrw.org/english/docs/2007/07/30/global16538.htm.

Grayson, George W. 2010. Mexico: Narco-Violence and a Failed State? New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

-------- 2008. “Los Zetas: The Ruthless Army Spawned by a Mexican Drug Cartel.” E-Notes, Foreign Policy Research Institute (May). Accessed November 30, 2013. www.fpri.org/enotes/200805.grayson.loszetas.html.

Green, Penny and Tony Ward. 2004. State Crime: Governments, Violence and Corruption. London: Pluto Press.

Hanson, Stephanie. 2008. “Mexico’s Drug War.” Council on Foreign Relations. November 20.

Hinton, Nicole and Daniel Montalvo. 2014. “Crime and Violence across the Americas” in The Political Culture of Democracy in the Americas, 2014: Democratic Governance across 10 years of the AmericasBarometer, Elizabeth K. Zechmeister, ed. Vanderbilt University, pp. 3–28.

Human Rights Watch. 2007. “Corruption, Godfatherism and the Funding of Political Violence.” Human Rights Watch. October. Accessed November 30, 2013. http://hrw.org/reports/2007/nigeria1007/5.htm.

Hung-En Sung. 2004. “State Failure, Economic Failure, and Predatory Organized Crime: A Comparative Analysis.” Journal of Research on Crime and Delinquency 41:111–129.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Husted, Bryan W. 1999. “Wealth, Culture, and Corruption.” Journal of International Business Studies 30 (2): 339–360.

Johnston, Michael J. 2014. Corruption, Contention, and Reform: The Power of Deep Democratization. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Karstedt, Susanne and Gary LaFree. 2006. “Democracy, Crime, and Justice.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 605 (May): 6–23.

Kaufmann, D. 2010. “The Big Question: Can Countries Break the Cycle of Crime and Corruption?” World Policy Journal, Spring.

-------- 2006. “Human Rights, Governance and Development: An Empirical Perspective.” Special Report. Development Outreach, 15–20. Accessed November 30, 2013. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTSITETOOLS/Resources/

Kelly, Robert J. 2003. “An American Way of Crime and Corruption.” In Roy Godson, ed. Menace to Society: Political Criminal Collaboration around the World, 99–136. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction.

Kurer, Oskar. 2005. “Corruption: An Alternative Approach to Its Definition and Measurement.” Political Studies 53: 222–239.

Lacey, Marc. 2008. “In Mexico’s Drug War, Sorting out Good Guys from Bad” NY Times November 2.

LaFree G. 1998. Losing legitimacy: Street crime and the decline of social institutions in America. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Le Billon, P. 2003. “Buying Peace or Fueling War: The Role of Corruption in Armed Conflicts.” Journal of International Development 15: 413–426.

Lessig, Lawrence. 2013. “Institutional Corruption,” Edmond J. Safra Working Papers, No. 1, Harvard University, Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, March 15.

-------- 2011. Republic Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress – and a Plan to Stop It. New York: Twleve.

Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Gabriel Salman Lenz. 2000. “Corruption, Culture and Markets.” In Culture matters: How values shape human progress, edited by Samuel P. Huntington and Lawrence Harrison, 112–124. New York: Basic Books.

Loftis, Matt W. 2014. “Deliberate Indiscretion? How Political Corruption Encourages Discretionary Policy Making.” Comparative Political Studies 1-31.

Lupsha, Peter. 1995. “Transnational Narco-corruption and Narco Investment: A Focus on Mexico.” Transnational Organized Crime 1 (1): 84–101.

Malone, Mary. 2013. “Does Crime Undermine Public Support for Democracy? Findings from the Case of Mexico.” The Latin Americanist 57 (2): 17–44.

de Maria, Bill. 2008. “Neo-colonialism through Measurement: A Critique of the Corruption Perception Index.” Critical Perspectives in International Business 4 (2/3): 184–202.

McGirr, Shaun. 2013. “Deliberate Indiscretion: Why Bureaucratic Agencies are Differently Corrupt.” American Political Science Association Meeting, Chicago, Aug. 29 – Sept 1.

Merkel, Wolfgang. 2012. “Measuring the Quality of Rule of Law: Virtues, Perils, and Results.” In Michael Zurn, Andre Nollkaemper, and Randall Peerenbook, eds. Rule of Law Dynamics in an Era of International and Transnational Governance, 21–47. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morris, Stephen D. 2014. “Corruption, Rule of Law, and Democratization in Mexico: Concepts and Boundaries.” XXXII International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, May 21-24, Chicago, IL.

-------- 2013. “The Impact of Drug-Related Violence on Corruption in Mexico.” The Latin Americanist 57 (1): 43–65.

-------- 2011a. “Mexico’s Political Culture, the Unrule of Law, and Corruption as a Form of Resistance.” Mexican Law Review 3 (2): 327–342.

-------- 2011b. “Forms of Corruption.” CESifo Dice Report 2: 10–14.

-------- 2009. Political Corruption in Mexico: The Impact of Democratization. Boulder: CO: Lynne Rienner.

Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. 2013. “Becoming Denmark: Historical Paths to Control of Corruption.” Social Research 80 (4): 1259–1288.

Naylor, R. T. 2003. “Predators, Parasites, of Free-Market Pioneers: Reflections on the Nature and Analysis of Profit-Driven Crime.” In Critical Reflections on Transnational Organized Crime, Money Laundering, and Corruption, edited by Margaret E. Beare, 35–54. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

-------- 2009. “Violence and Illegal Economic Activity: A Deconstruction.” Crime, Law and Social Change 52: 231–242.

Nueman, W. Lawrence and Ronald J. Berger. 1988. “Competing Perspectives on Cross-National Crime: An Evaluation of Theory and Evidence.” The Sociological Quarterly 29 (2): 281–313.

Nye, Joseph S. 1967. “Corruption and Political Development: A Cost-Benefit Analysis.” American Political Science Review 61: 417–27.

O’Day, Patrick and Aneglina López. 2001. “Organizing the Underground NAFTA.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 17 (3): 232–242.

O’Day, Patrick. 2001. “The Mexican Army as Cartel.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 17: 278–295.

O’Donnell, Guillermo. 2004. “Why the Rule of Law Matters.” Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 32–46.

-------- 1999. “Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies.” In The Self-Restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies, edited by Andreas Schedler, Larry Diamond and Marc Plattner, 29–52. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

O’Neil, Shannon. 2009. “The Real War in Mexico.” Foreign Affairs 88 (4): 63–77.

“Organized Crime Highlights Corruption in Some Latin American Countries.” 2011. Catholic Review, October 16. Accessed November 20, 2013. http://catholicreview.org/article/work/business-news/organized-crime-highlights-corruption-in-some-latin-american-countries.

Pansters, Wil G., ed. 2012. Violence, Coercion, and State-Making in Twentieth-Century Mexico: The Other Half of the Centaur. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Pimental, Stanley A. 2003. “Mexico’s Legacy of Corruption.” In Menace to Society: Political Criminal Collaboration around the World, edited by Roy Godson, 175–198. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction.

Pratt, Travis C & Francis T Cullen. 2005. “Assessing macro-level predictors and theories of crime: A meta-analysis.” Crime and Justice 32: 373–449.

Reyes, Leonarda. 2006. “Reporters Notebook: Mexico” Global Integrity 2006 Country Reports. Accessed October 10, 2013. www.globalintegrity.org/reports/2006/mexico/notebook.cfm.

Rios, Vidriana. 2011. “Why are Mexican Mayors Getting Killed by Traffickers? A Model of Competitive Corruption.” Unpublished.

Rock, Michael T. 2009. “Corruption and Democracy.” Journal of Development Studies 45 (1): 55–75.

Roh, Sunghoon and Ju-Lak Lee. 2013. “Social Capital and Crime: A Cross-National Multilevel Study.” International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 41: 58–80.

Rothstein, B. and Teorell, J. 2008. “What Is Quality of Government? A Theory of Impartial

Government Institutions.” Governance 21 (2): 165–190.

Rubio, Luis. 2015. A Mexican Utopia: The Rule of Law is Possible. Washington, D.C.: Wilson Center.

Sabet, Daniel. 2010. “Police Reform in Mexico: Advances and Persistent Obstacles.” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Mexico Institute, Working Paper Series on U.S.-Mexico Security Collaboration.

Sandoval-Ballesteros, Irma E. 2013. “From ‘Institutional’ to ‘Structural’ Corruption: Rethinking Accountability in a World of Public-Private Partnerships.” Edmond J. Safra Working Papers. No. 33. Harvard University.

Schneider, Friedrich and Andreas Buehn. 2009. “Shadow Economies and Corruption All over the World: Revised Estimates for 120 Countries” Economics: The Open-Access, Open-assessment E-Journal.

Shelley, Louise. 2005. “The Unholy Trinity: Transnational Crime, Corruption, and Terrorism.” Brown Journal of World Affairs 11 (2): 101–111.

-------- 2001. “Corruption and Organized Crime in Mexico in the Post-PRI Transition.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 17 (3): 213–231.

Shirk, David. 2010. “Drug Violence in Mexico: Data and Analysis from 2001-2009.” Trans-Border Institute.

Snyder, Richard and Angelica Duran-Martínez. 2009. “Does Illegality Breed Violence? Drug Trafficking and State-Sponsored Protection Rackets.” Crime, Law, and Social Change 52: 253–273.

Soares, Rodrigo R. 2004. “Crime Reporting as a Measure of Institutional Development.” Economic Development and Cultural Changes 52 (4): 851–871.

Tamanaha, Brian Z. 2004. On the Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, Dennis F. 2013. “Two Concepts of Corruption,” Harvard University, Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, Working Papers, No. 16, August 1.

-------- 1995. Ethics in Congress: From Individual to Institutional Corruption. Washington, DC: Brookings.

Tilly, Charles. 1985. “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime.” In Bringing the State Back In, edited by Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol, 169–186. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tromme, Mathiew and Miguel Angle Lara Otaolo. 2014. “Enrique Peña Nieto´s National Anti-Corruption Commission and the Challenges of Waging War against Corruption in Mexico.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 30 (2): 557–588.

Triesman, Daniel. 2007. “What Have We Learned about the Causes of Corruption from Ten Years of Cross-National Empirical Research?” Annual Review of Political Science 10: 211–244.

Uildriks, Niels. 2009. “Policing Insecurity and Police Reform in Mexico City and Beyond.” In Policing Insecurity: Police Reform, Security, and Human Rights in Latin America, edited by Niels Uildriks, 197–224. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Uslaner, Eric M. and Bo Rothstein. 2013. “The Roots of Corruption: Mass Education, Economic Inequality and State Building.” American Political Science Association.

Uslaner, Eric M. 2008. Corruption, Inequality, and the Rule of Law. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Van Dijk, Jan. 2007. “Mafia Markers: Assessing Organized Crime and its Impact upon Societies.” Trends in Organized Crime 10: 39–56.

Warren, Mark E. 2006. “Political Corruption as Duplicitous Exclusion.” PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (4): 803–807.

-------- 2004. “What Does Corruption Mean in a Democracy?” American Journal of Political Science 48 (2): 328–343.

Widner, Benjamin, Manuel L. Reyes-Loya and Carl E. Enomoto. 2011. "Crimes and Violence in Mexico: Evidence from Panel Data." The Social Science Journal 48 (4): 604–611.

Wilson, James Q., ed. 2013. Thinking about Crime. Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books.

Xin, Xiaohui and Thomas K. Rudel. 2004. “The Context of Political Corruption: A Cross-National Analysis.” Social Science Quarterly 85 (2): 294–309.

Yankah, Ekow N. 2013. “Legal Vices and Civic Virtue: Vice Crimes, Republicanism and the Corruption of Lawfulness.” Crime, Law and Philosophy 7: 61–82.

You, Jong-sun and Sanjeev Khagram. 2005. “A Comparative Study of Inequality and Corruption.” American Sociological Review 70: 136–157.

Zechmeister, Elizabeth K., ed. 2014. The Political Culture of Democracy in the Americas, 2014: Democratic Governance across 10 years of the AmericasBarometer, Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University.

Zepeda Lecuona, Guillermo. 2004. Crimen sin castigo: Procuración de justicia penal y Ministerio Público en México. Mexico City: Centro de Investigación para el Desarrollo and Comisión Federal de Electricidad.

Zechmeister, Elizabeth J. and Daniel Zizumbo-Colunga. 2010. “The Political Toll of Corruption on Presidential Approval.” Americas Barometer Insights.

Zúñiga M., Juan Antonio. 2014. “Impunes, 93.8% de los delitos perpetrados en 2013: Inegi.” La Jornada 30 de septiembre. Accessed February 15, 2015. http://www.jornada.unam.mx/ultimas/2014/09/30/en-primer-ano-de-gobierno-de-epn-quedaron-impunes-93-8-de-delitos-perpetrados-3893.html.

About the author

Steven D. Morris is Professor of Political Science at Middle Tennessee State University.

1. Many of the ideas in this paper were initially explored in Morris (2011a).↩

2. The scope here is limited to the issue of causality. The consequences of crime and corruption are huge, of course, ranging from the human costs (fear among the people, political and civic frustration, vigilantism, and reduced rates of economic growth) to the lack of interpersonal confidence, trust in the state, presidential approval, and even popular support for democracy (see Booth and Seligson 2009; Bateson 2010; Hinton and Montalvo 2014; Karstedt and LaFree 2006; Zechmeister and Zizumbo-Colunga 2010).↩

3. Many would argue that providing security constitutes the primary function of government. Whether authority is delegated via some sort of Hobbesian or Lockean social contract or acquired through a negotiated process by which an organized criminal group creates an effective and stationary protection racket (Tilly 1985), states are expected to utilize their power to protect people and property from harm by insiders and outsiders. This expectation constitutes, in turn, the foundation of the “legitimacy” people bestow on the state that, in a Weberian sense, qualifies and differentiates the state’s so-called monopoly of coercive force from the force exercised by others (challengers). The state, it should be stressed, does not simply enjoy a “monopoly of coercive force” within a territory since individuals and groups also utilize force for civil, criminal, or political purposes. What distinguishes the state from others is that the state’s use of coercive power is deemed “legitimate” or a priori appropriate by the public. Moreover, the state plays a role in shaping the contours of its own legitimacy through education and controls on social communication. To be sure, even the state’s use of coercive force in specific instances is not always considered legitimate and the state can and often does abuse its authority. As Green and Ward (2004, 1) note, the difference between robber barons and states without justice is “states claim the power to determine what is ‘just’” (Green and Ward 2004, 1).↩

4. Joseph Nye’s (1967) often used definition characterizes corruption as “behavior which deviates from the formal duties of a public role because of private regarding (personal, close family, private clique) pecuniary or status gains.” Michael Johnston (2014, 9) similarly defines corruption as “the abuse of public roles or resources for private benefit.” Rather than seeing corruption as a specific form of behavior tied to private gain, however, more recent definitions adopt broader, more systemic views that not only reach beyond private gain to include institutional and political gain, but also reach back to earlier, classical views that saw corruption as a systemic rather than a purely behavioral phenomenon. This includes Thompson’s (1995, 2013) and Lessig’s (2011, 2013) notions of institutional corruption where covert institutional norms—often legal exchanges—undermine an institution’s purpose (Warren 2004, 331;), Kurer’s (2005) or Rotherstein and Teorell’s (2008) emphasis on the impartial or nonuniversal implementation of public policy to define corruption, McGirr’s (2013) notion of deliberate indiscretion, Warren’s (2006) definition of corruption as the duplicitous exclusion in the making of policy by those affected by it, or Sandoval-Ballesteros’s (2013, 9) broad structural definition of corruption as a “specific form of social domination characterized by abuse, simulation, and misappropriation of resources arising from a pronounced differential in structural power.”↩

5. In defining state crime, Green and Ward (2004, 5-6) emphasize the operative goals of the state organization. This leads them to initially exclude corruption from state crime, though they later note that if the state allows certain acts, including corruption, that contribute to an organizational goal, even if this is not the motivation of the individual acting, then it constitutes organizational deviance.↩

6. Such broad concepts raise the question of whether these components are internally correlated. There is some evidence of this. Kaufmann (2006, cited in Beyerle 2011), for example, links corruption to impunity, Ganesan (2007; cited in Beyerle 2011) ties it to repression, while Lofti (2014) and Uslaner (2008) link corruption at the higher levels of government (political corruption) to corruption at the lower levels (bureaucratic or petty corruption).↩

7. There are many examples of these activities in Mexico throughout the years (see SourceMex 2006-07-26 and 2008-09-03). Citing statistics from the SSP (Security Ministry), Excelsior reported, for example, that 56 of the 897 kidnappers arrested from 2001 through the first half of 2008 were active or former members of a police department or the military (SourceMex September 24, 2008) This blurring of the lines can also be seen in revolving-door corruption where state officials leave office to work for the companies they had been policing. This is common in the white-collar world where former regulators leave office to take positions in the industries they once regulated, or even former police or military joining organize crime. Many former police and military officers in Mexico have gone on to pursue careers with DTOs (Grayson 2008, 2010).↩

8. While the offering of a bribe is a criminal act, it is important to note that it may not always result in corruption since not all offers are accepted, nor are all bribes reciprocated with the public official delivering his/her part of the corrupt bargain.↩

9. I (Morris 2014) contend that corruption itself is embedded in our conceptualizations of the rule of law and democracy. As a brief example, Guillermo O’Donnell (1999, 307) defines what he labels democratic rule of law as when the law is “fairly applied” and that its application is consistent “without taking into consideration the class, status, or power differentials of the participants….” Surely this definition incorporates corruption since by definition corruption involves violating the norms of official decision-making by taking into consideration factors like the power or money of others and is thus not fairly applied. Among other effects, embedded conceptualizations like this make it difficult to even contemplate the relationship between corruption and democracy, as many studies do, since corruption by definition is part of the absence of rule of law and democracy.↩

10. Even those who, like Warren (2006), differentiate rule of law from corruption, nonetheless seem to cast corruption as undermining the rule of law within the government rather than in society: The “harm to democracy [from corruption] is that the rule of law becomes less certain, excluding citizens from legal rights, protections and securities to which they are entitled” (Warren 2006, 805).↩