DOI 10.18413/2312-3044-2016-3-2-106-113

TURKISH PRISONERS OF WAR IN THE BELGOROD PROVINCE

DURING THE RUSSIAN-TURKISH WAR OF 1768–74 *

Vitalii V. Poznakhirev

Smolny Institute, Russian Academy of Education (St. Petersburg)

Abstract. This article examines the role of the Belgorod Province in the evacuation and internment of enemy POWs during the Russian-Turkish War of 1768–74. The author quantifies the number of the POWs, indicates their quartering sites and placement difficulties; examines financial, material, and other questions regarding their provision, and explores their daily lived experience. He concludes that the Belgorod Province authorities made a significant contribution to the improvement of both the process and legislative framework for the naturalization of former Turkish prisoners in Russia.

Keywords:Russian-Turkish War, Belgorod Province, prisoners of war, the Turks, internment, provision, prisoner transfer, naturalization.

Copyright: © 2016 Poznakhirev. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source, the Tractus Aevorum journal, are credited.

Correspondence to: Vitalii V. Poznakhirev. Smolny Institute of Russian Academy of Education, Department of Humanities. 195197, Poliustrovskii pr. 59, St. Petersburg, Russia. E-mail: vvkr[at]list.ru

УДК 94(47).066.2

ТУРЕЦКИЕ ВОЕННОПЛЕННЫЕ В БЕЛГОРОДСКОЙ ГУБЕРНИИ

В ПЕРИОД РУССКО-ТУРЕЦКОЙ ВОЙНЫ 1768–1774 гг.

Аннотация. В статье раскрываются роль и значение Белгородской губернии в эвакуации и интернировании военнопленных противника в период русско-турецкой войны 1768–1774 гг. Автор приводит количественный состав пленных; называет пункты их расквартирования и дает обзор трудностей, с которыми сталкивались власти Белгородской губернии при решении данного вопроса; освещает вопросы финансового, вещевого и иных видов обеспечения османских пленников, а также некоторые аспекты повседневной жизни военнопленных. Особо подчеркивается вклад руководства губернии в совершенствование как законодательной базы, так и порядка натурализации в России бывших турецких военнопленных.

Ключевые слова: русско-турецкая война, Белгородская губерния, военнопленные, турки, интернирование, обеспечение, этапирование, натурализация.

In September 1769, the Military Collegium informed the Belgorod governor of its decision to send captive Turks and Tatars from the general assembly point for POWs in Kiev “to Voronezh, Belgorod, Vladimir, and Novokhopersk fortress in parties of fifty to one hundred people by the most convenient routes, allowing up to five hundred people in each place, with an equal number in each place, where they (except for women and small children[1]) are to be used in fortification and community works.”[2]

Besides the fact that this decision was made only a year after the outbreak of the war with Turkey, it seems that it was not based on a preliminary agreement with the authorities of Belgorod Province and, moreover, was a complete surprise for them. Characteristic in this regard is the report of the commander from October 6, 1769. Assuring the collegium that Belgorod will take as many POWs as required, he then tried to immediately disavow his own statement, stressing that:

- “the town has burned down,” and the surviving buildings “are being rebuilt according to the plan; adding Turks and Tatars there would make it extremely cramped;”

- although there is a prison in town, it only has two log cabins;

- the proximity of the town to the Ukrainian front requires enhanced escort for the prisoners, whereas “nearly all of the garrison battalion is dispersed on different missions so that the remaining troops change guards only every three and sometimes every four weeks.”[3]

Even so, the collegium remained relentless and, confirming its previous decision, demanded that the commander “make every effort” to accommodate the prisoners. The only thing it conceded was the agreement to consider the transfer of the Turks and Tatars to some other towns of the province in the event that “the multitude (of POWs—V.P.) would cause untenable overcrowding.”[4]

On December 17 (other sources date it as December 19 or 22), 1769, one hundred prisoners arrived in Belgorod for permanent quartering, and seventy-five more on January 11. The first thing the authorities in Russian cities encountered in such cases was the lack of an interpreter. However, it seems that this problem had been considered in advance in Belgorod, as from the very first day of the prisoners’ arrival, a local craftsman, Ivan Panfilov, himself a former Turkish prisoner who had converted to Orthodoxy and remained in the province after the previous Russian-Turkish War of 1735–39, was put in charge of the prisoners. The governor of Belgorod A. M. Fliverk used his authority to set a salary for the interpreter, as it was not provided by any regulations, and convinced the Military Collegium to accept his decision. He argued that Ivan Panfilov, who now lacked the time to engage in his craft, was “in extreme need of subsistence.” He noted that in addition to his direct duties, Ivan “teaches willing prisoners to profess the Greek faith, and is qualified to do so as a long-time resident in Russia; it is utterly impossible to get by without him.”[5]

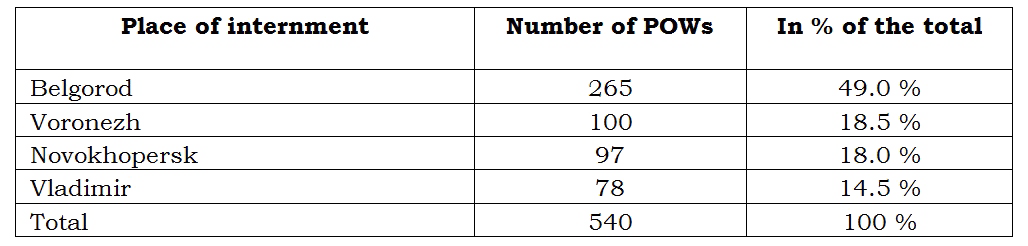

Much more acute in Belgorod was the problem of quartering the POWs. In accordance with the law and practice of those years, they were placed in the city jail, together with the convicts. However, due to the continuous influx of new parties of Turks and Tatars, the facility’s capacity was quickly exhausted. The situation deteriorated further due to a somewhat specific approach to the distribution of POWs by “the staff” of the Kiev Governor-General, which is clear from the data in Table 1.

Table 1

Distribution of POWs admitted at the general assembly point in Kiev

to places of internment (as of September 27, 1770)[6]

By July 1770 the governor was forced to ask the Military Collegium to suspend the internment of Turks to Belgorod. For some time, the influx of prisoners to the city ceased, and some prisoners were even transferred to other regions. However, in fall 1770, the system “came full circle.” On November 6, 141 POWs arrived in town, and on November 22, 90 more appeared, who were put in jail “with great difficulty,” due to the “consolidation” of the Russian convicts. On November 25, the commander of the town reported to the governor that “Turk and Arab captives contained in Belgorod amount to 357 people and, due to the lack of barracks, are greatly cramped and many spend the night in the jail yard. Owing to the current rainy season, they suffer from cold and exhaustion, and constantly ask through the interpreter for reconsideration.” The commander then expressed concerns that in the coming winter, the situation will deteriorate and the prisoners “may, God forbid, come to sickness from the damp and stale air.”[7]

At precisely that moment in November 1770, without getting permission from the Military Collegium for a partial transfer of prisoners to other cities, A. M. Fliverk used his authority to distribute groups of forty-fifty Turks to Kursk, Korocha, Karpov and Oboian’. Later, the list expanded to other settlements in the province.

Despite this action, the harshness of the “accommodation problem” only somewhat waned in mid-1772 after Russian annexation of Crimea, when the Military Collegium demanded the removal of POW status from all Crimean Tatars and Tatars of the Budjak, Edisan, Edikul, and Jumbalat hordes, and “their escort back to their homes, along with standard reimbursement for food.” [8] Even earlier, in late 1771, the same decision was made with regard to captured Turkish Armenians, Greeks, and Jews, who were instructed to be sent for settlement in Kremenchug.[9]

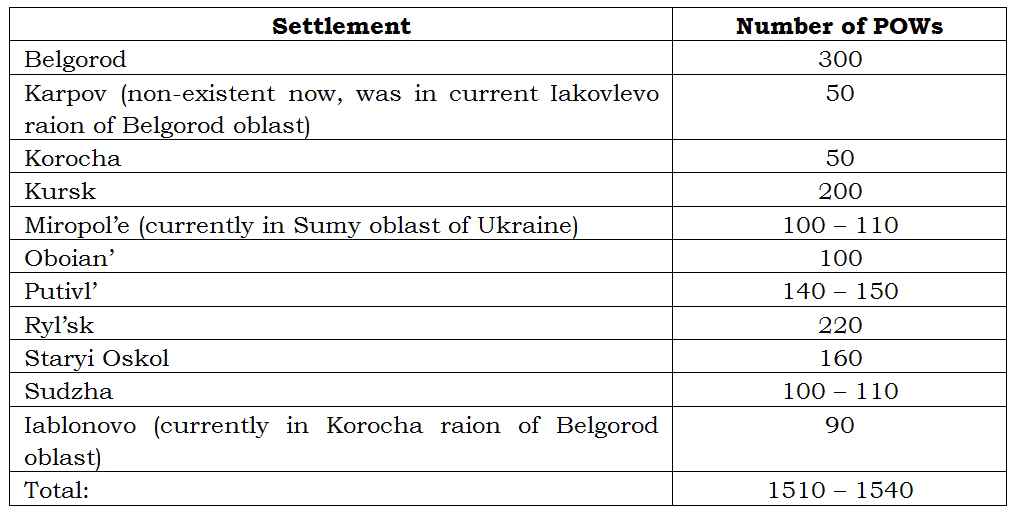

However, as shown in Table 2, by July 10, 1774, i.e. at the time of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca that ended the Russian-Turkish War of 1768–74, the total number of Turks in the province was at least three times higher than the 500 people originally planned for by the Military Collegium.

Table 2

Approximate number of Turkish POWs

stationed in the territory of Belgorod Governorate

(as of July 10, 1774)[10]

Given the fact that the POWs were unaccustomed to the traditional food of a Russian soldier, they received monetary compensation rather than food at a rate of three kopecks a day, “so that they could buy themselves what they wished and could thus nourish themselves.” When the Turks were employed in public works, another kopeck was added to the daily sum. If the prisoners were hired to work for private individuals, their additional payments depended on the will of the employer. Thus, the author N. Kokhanovskaia (N. S. Sokhanskaia) recalled that her great-grandfather, who lived near Korocha, “hired captive Turks, who dug ponds in Khvoshchevatoe and an entire lake for the winery in Bekhteevka.” Kokhanovskaia also indicated that the Turks were fed at the expense of the employer and also received two kopecks per day for their work, while the price of a bag of rye flour was six kopecks (1886, 13).

Clothing allowance for the POWs included both summer and winter clothing. In particular, the latter consisted of a sheepskin coat, hat, shirt, warm trousers, boots, and homespun cloth for leggings. Due to a shortage of personnel, the escort of Turkish POWs to places of internment was carried out by armed townsfolk (primarily retired soldiers).

Besides the direct placement of prisoners on its territory, Belgorod province also functioned as a transit region through which the POWs were escorted to Voronezh province, mainly via “Belgorod—Valuiki” and “Sudzha—Oboian’—Staryi Oskol—Ostrogozhsk” routes.[11] In such cases, the POW contingents were joined by specially appointed commissioners on the border of the province, whose task it was to make sure “that no commoner was offended while the parties passed by.” Local authorities and the local population were required to provide carts “for the exhausted and sick prisoners,” and, if necessary, to provide people to support the convoy “with possible shifts from the garrison.” In addition, instructions dictated the dispatch to the settlements along the escort routes of “as much food as possible for camp followers, or let the residents prepare white bread and other food that they could sell at a profitable price so that the prisoners were delivered from these needs.” At night, it called for the placement of the Turks in huts “and leave them locked there on their own, guarded by the commoners.”[12]

The highly organized nature of work with POWs in the province is indicated by the fact that during the six years of war, despite the proximity of the border, only one successful (though collective) escape from its territory occurred, dated August 1770.[13]

It should be noted that during their time in Belgorod, a number of Turkish prisoners converted to Orthodoxy and became Russian subjects. Thus, already on February 11, 1770, Bishop Samuil of Belgorod wrote to the Holy Synod that “Turk Mehemet Uzer oglu, who was sent with the first party of captives from Kiev, . . . is willing to accept the Greek Orthodox confession of faith through no coercion whatsover.” Then the bishop asked the Synod for a “special decree” concerning what he should do in such cases, taking into account the fact that Turkey and Russia were at war.[14] Almost simultaneously with the bishop’s letter, A. M. Fliverk raised the same matter with the Military Collegium. The result of their joint efforts was the decree of Catherine II on April 20, 1770, “On the pronouncement of captured Turks and Tatars who accept the Greek-Russian faith as free people and leaving them to choose their way of life.”[15] This most important document determined the fate of naturalized Turkish POWs in Russia for nearly a century.

Further, according to our estimates, in 1771 the governor of Belgorod was the first to introduce the practice of “special placement” to ensure the safety of Turkish prisoners who were willing to convert to Orthodoxy. Apparently it was due to this requirement that the janissary Ahmed, detained in Staryi Oskol, was baptized in 1774 a few dozen miles away in Manturovo (now the regional center of Kursk oblast).[16] In the context of naturalization, Makhmet Bek (in Orthodoxy: Pavel Petrovich Bek) deserves special attention. He was baptized in Belgorod in late 1770 and then voluntarily enlisted as a private in the Akhtyrka hussar regiment.[17]

As for the repatriation of the Turks from the province, it was uneventful and mostly completed by April 1775, i.e. before the end of the spring thaw. However, in November the Turkish government filed claims with Russia, alleging that thirty former Turkish prisoners of war were illegally being held in Belgorod, and even listed their names. The head of the Collegium of Foreign Affairs demanded that the governor “find out whether the aforementioned Turks are kept anywhere.” The audit showed that twenty-two people from the list had adopted the Orthodox faith and, according to the requirements of Article 25 of the Küçük Kaynarca Peace Treaty, were not subject to repatriation. In regard to an additional seven people, no information was found. There was only one person staying in town illegally, Belekli (Baloch) Ismail, who lived in Belgorod of his own will and apparently had already managed to start “his own business” there and thus did not hurry home.[18]

Summarizing the above, it is possible to draw the following conclusions: 1. During this period, the authorities of Belgorod Province successfully coped with the tasks concerning the reception, accommodation, and further evacuation of enemy prisoners of war. During the war, about 25 percent of all Ottoman prisoners were stationed in the province, and about the same amount passed through the territory to Voronezh Province. 2. The organization of work with captive contingents in Belgorod ensured acceptable conditions, even in the face of a small number of convoys and the acute shortage of accommodation. It also managed to avoid outbreaks of infectious diseases and minimize prisoner escapes. 3. The authorities of the Belgorod province made a significant contribution to the improvement of both the process and legislative framework for the naturalization of former Turkish prisoners in Russia.

Translated from Russian by Alexander M. Amatov

References

Kokhanovskaia, N. [N. S. Sokhanskaia]. 1886. Starina. Semeinaia pamiat’. St. Petersburg: Tipografiia A.S. Suvorina.

Polnoe sobranie zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii [Complete Collection of the Laws of the Russian Empire]. Sobr. 1. Vol. XIX. No 13540.

About the author

Vitalii V. Poznakhirev, Candidate of Science (History), is Associate Professor with the Department of Humanities, Smolny Institute, Russian Academy of Education (St. Petersburg).

*The Russian version of this article was published: Poznakhirev, V. V. 2013. “Turetskie voennoplennye v Belgorodskoi gubernii v period russko-turetskoi voiny 1768–1774 gg.” Belgorod State University Scientific Bulletin. Series History. Political Science 26 (8): 89–93. ↩

1. Apart from women and children, officers were also excused from the works.↩

2. Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv drevnikh aktov [Russian State Archive of Early Acts] (RGADA). Fond 248. Opis` 67. Kniga 5951. List 104.↩

3. Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi voenno-istoricheskii arkhiv [Russian State Military History Archive] (RGVIA). Fond 16. Opis` 1. Delo 1854. List 3.↩

4. Ibid. L. 4.↩

5. RGVIA. F. 16. Op. 1. D. 1866. L. 1-3.↩

6. Made according to: RGVIA. F. 16. Op. 1. D. 1855. L. 6.↩

7. RGVIA. F. 16. Op. 1. D. 1865. L. 1-2.↩

8. Ibid. D. 1862. L. 232.↩

9. Tsentral'nyi gosudarstvennyi istoricheskii arkhiv Ukrainy v Kieve [Central State History Archive of Ukraine in Kiev] (TsGIAK Ukrainy). Fond 1710. Opis` 2. Delo 893. List 4.↩

10. Made according to: RGVIA. F. 16. Op. 1. D. 1865. L. 1-2; RGADA. F. 580. Op. 1. D. 5284. L. 6; TsGIAK Ukrainy. F. 54. Op. 3. D. 9329. L. 2; F. 59. Op. 1. D. 7839. L. 10, 13; D. 7844. L. 18, 27; D. 7850. L. 1. ↩

11. TsGIAK Ukrainy. F. 59. Op. 1. D. 6858. L. 1.↩

12. TsGIAK Ukrainy. F. 1710. Op. 2. D. 893. L. 1-2.↩

13. Ibid. F. 59. Op. 1. D. 6232. L. 1.↩

14. Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi istoricheskii arkhiv [Russian State History Archive. Fond 796. Opis` 51. Delo 77. List 1-2.↩

15. Polnoe sobranie zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii [Complete Collection of the Laws of the Russian Empire]. Sobr. 1. Vol XIX. No 13540.↩

16. RGADA. F. 580. Op. 1. D. 5284. L. 1-3.↩

17. RGVIA. F. 16. Op. 1. D. 1862. L. 134-140.↩

18. Arkhiv vneshnei politiki Rossiiskoi Imperii [Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Empire]. F. 2. Opis` 1/2. Delo 1256. List 178-187. ↩